by Subhuti Dharmananda, Ph.D., Director, ITM

Q. Why did warning labels suddenly appear on Seven Forests and other ITM products sold to California?

A. The products have not changed. Californians passed Proposition 65 (a regulation calling for warning labels and signs) in 1987 and this regulation is gradually being enforced through legal actions initiated by some California citizens. Enforcement frequently results in application of a warning label like the one that has appeared on the bottles of ITM products regarding lead content. Application of Proposition 65 to Chinese herb products began in 2001, first involving companies based in California and then spreading to companies outside of California who ship products into California. ITM had not previously utilized this label due to misunderstanding about the applicability of Proposition 65 to its materials; public notification about Proposition 65 has been limited, most likely because legal cases have dominated the enforcement method, as opposed to educational programs and advisory notices.

Q. So, does this mean that ITM products are dangerous?

A. The warning labels required by Proposition 65 do not present information about the safety or the risk of the products; the warning about lead does not specify the actual amount of lead that is present or whether any particular amount is harmful. The requirement for a warning label is triggered when the amount of a regulated substance in a product exceeds a certain regulatory level, which is very low in the case of lead. According to the way Proposition 65 is worded and with the limited data about effects of exposure to lead, the labeling must be done if the total daily lead intake exceeds just 0.5 micrograms (µg). For Seven Forests products, as an example, the labels indicate a recommended daily dose of 6–9 tablets per day. At 9 tablets per day (700 mg tablet size), the lead content of the herb material would have to be less than 0.08 parts per million (ppm = micrograms/gram) to avoid carrying a warning label [to give a sense of parts per million, using examples from the water bureau in reporting lead content of drinking water, 0.08 ppm represents 2.5 seconds out of a year; it represents 8 cents out of a million dollars]. Ordinary commercial testing for lead in food products can only detect lead down to the level of 0.5 ppm, so special high-resolution testing (which is very expensive and only carried out by a few laboratories) is required to assure any product meets allowable levels. By contrast, international regulations call for lead levels in herbs to remain below 10 ppm, with the strictest standards (outside of California’s Proposition 65) being 3 ppm in finished products; these amounts are readily detected by routine tests. So, the Proposition 65 standard is set far below the lead levels allowed anywhere else and is not based on scientific analysis of actual risks, but on a regulatory system contained within the Proposition.

Q. But, doesn’t lead cause cancer and reproductive harm, like the label says?

A. Proposition 65 regulates substances for which harm is shown under any circumstances, such as experiments with laboratory animals or when humans are exposed under unusual circumstances. As an example, the California EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) has determined that lead is a carcinogen in laboratory animals when lead acetate (a more soluble form of lead than is often found in nature) is fed in substantial quantities. Lead tends to accumulate in the kidneys of these animals and eventually causes cancer of the kidneys. EPA has not determined whether lead is a carcinogen for humans; to determine that, it has examined data from humans working in heavily contaminated factories that process lead; kidney cancer has not been observed as a result of such exposures, and there is conflicting data as to whether such workers experience more cancers than others. The factories are cleaner now, so getting new human data is no longer possible. The label provides the standard wording for the Proposition 65 lead warning.

Q. Why do your products have this warning, but many other products with Chinese herbs do not?

A. Proposition 65 labeling requirements are not uniformly utilized. For example, if a company has fewer than 10 employees, it is exempt from the requirement to include warning labels; many Chinese herb manufacturers and distributors have fewer than 10 employees. A method of avoiding warning labels is to undertake a legal challenge to the applicability of Proposition 65. One company in California invested heavily in bringing experts from China to testify in court that the lead content of the Chinese herbs could be explained entirely from natural sources, which allows for another exemption from Proposition 65 labeling; the judge in the case determined that they had demonstrated the point, so they did not require labels on their products (but the judgment applied only to their products). Some companies have not yet received a Proposition 65 action, so have not applied the labels. ITM has more than 10 employees (though most of its employees are part time medical workers providing acupuncture and related therapies) and ITM does not have the funds necessary to enter into a court case over this matter. ITM does not object to compliance with Proposition 65, despite its position that the required labels are misleading rather than informative.

Q. Is the lead in the products from natural sources?

A. The answer to this is complex. Lead is a natural component of the soil, and measurements of soil lead levels around the world have been made, indicating some natural variability by location. However, for more than 2,000 years, human activity has affected the soil levels of lead in some areas, and this accelerated greatly during the 20th Century. Vast amounts of lead have been taken from the earth, distributed into the atmosphere, eventually getting into the soil, where it is then taken up into plants. Probably the biggest single redistribution of lead came about from use of leaded gasoline. As the gasoline was burned in vehicles, the exhaust carried the lead into the atmosphere, and the lead rained down onto the soil. Leaded gasoline was gradually phased out, beginning in 1970 in the U.S. (the largest user of leaded gasoline at the time), and is now no longer produced, but some lead from the burned fuel remains in the surface soil. Similarly, when coal is burned, the lead that it naturally contains goes up the smoke stack and into the atmosphere. Coal burning remains a major source of energy (little used in the U.S., but heavily relied upon in many countries). Other sources of atmospheric lead involve factories manufacturing products, such as making lead batteries used in cars and trucks, or for making lead-crystal glass. Some of the soil’s lead was “there from the beginning” but some of it comes from human activity, and especially from modern human activities. No lead is intentionally added to the soil where the herbs are grown or to the herb products during manufacture; rather, the lead is taken up by the plants from what is already in the soil, which is not necessarily any different than soil elsewhere. So, in the sense that the lead is ordinarily part of the soil, it is of natural origin; but because a portion of the lead in the soil arrived there after being redistributed through human activity, in that sense some is not natural. A few years ago, there was a report about heavy metal contamination of imported “patent medicines” from China. The metals involved in those cases came from intentionally added traditional substances that are never used in American-made products, and from Chinese factories that had contamination problems (which have now been remedied and which had not affected American-made products).

Q. What level of lead is in ITM products?

A. The lead level of ITM products will vary somewhat from batch to batch, since the herb materials come from a wide geographic area; the herbal ingredients are different from product to product, since different plants take up lead at different rates. Factors affecting lead uptake by plants include not only their species and the amount of lead in the soil, but the acidity of the soil which is affected by numerous factors. Lead becomes more concentrated in roots and barks (that have a richer content of lead-binding substances) than in the leaves and flowers of most plants and Chinese herbalists rely especially on root and bark portions of plants. Chinese “herbs” may also include some animal source materials and some natural minerals; animals accumulate lead from the plants they eat, which enters the bones, shells, and other calcium structures, some of which are used by Chinese herbalists; natural minerals can also include lead in their total composition. Over many years, ITM has performed random tests of its herb tablets and also has had access to data from testing done by other companies, for both raw materials and finished products (see sample data below). Lead levels in ITM products are similar to those found in other Chinese herb products manufactured in the U.S., and the usual range is 0.15 to 1.5 ppm in a finished product, with an average value around 0.8 ppm. As described, in order to meet Proposition 65 limits, the maximum level would have to be 0.08 ppm, a level not attainable. ITM products meet the standards relied upon by all other countries, including the U.S., except for the unusual requirements of Proposition 65.

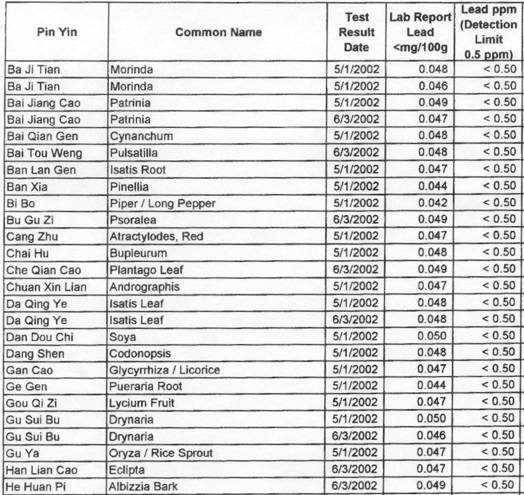

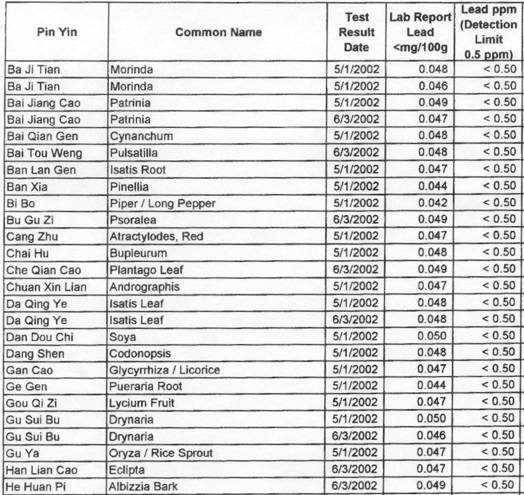

Table 1. Sample data from raw materials used in manufacture of U.S. Chinese herb products. These tests were conducted during May and June 2002, often using more than one batch of an herb (when available). Because the data are below the detection limit of 0.5 ppm (or 0.05 mg/100 g), the data simply show values just below that. However, the actual amount may be even lower.

Table 2. Comparing U.S. produced finished product with that from China: the ITM (Pine Mountain brand) substitute is called Kang Ning Pian, the original name for imported Pill Curing (Culing). Testing of the ITM product by Food Products Laboratory (FPL) shows markedly lower lead and arsenic than in the patent.

Tested Product |

Lead |

Arsenic |

Pill Curing, FDB test reported in 1998, Yang Cheng brand (imported) |

1.8 ppm |

1.1 ppm |

Pill Culing FPL test conducted in 2003, Yang Cheng brand (imported) |

1.2 ppm |

0.7 ppm |

Kang Ning Pian test conducted in 2003, Pine Mountain (ITM) |

0.5 ppm |

0.3 ppm |

Q. What is my risk from lead I might get by taking Chinese herbs?

A. The risk is unknown. The lead in herb products is not more or less risky than lead found in the American diet, which is reported to provide about 15–25 ug of lead per day or more (the lead comes mainly from plant foods); just a decade or two ago, that figure was ten times higher and in the 1970s it was twenty times higher. There is no doubt that very high lead exposure can be harmful, especially to young children, but these low levels of lead as found in foods and herbs are difficult to analyze in terms of either short term or long term risk. At 9 tablets per day of Seven Forests formulas, with an average value of 0.8 ppm, the amount of lead intake would be about 5 ug of lead in a day. Though there is no means by which one can assure that 5 ug of lead would be “safe,” it is a quantity consistent with ordinary daily dietary exposure (see appendix, below, for sample of food analysis). Pregnant women ought to minimize their exposure to lead from all sources, since the developing fetus would be most sensitive to its effects, so use of Chinese herbs during pregnancy ought to be minimized (ITM recommends this also because of the ordinary organic herbal components to which a fetus might be sensitive). The particular materials used in Chinese medicine may have lead levels that are either higher (or lower) than common food items proportionate to the amount consumed, but specific data are hard to come by. In a study of 10 mushroom species obtained from Tokat, Turkey, the highest level of lead was found in Fomes fementarius (one of the mushrooms used in traditional Chinese medicine), at 2.7 ppm. Medicinal mushrooms typically grow on trees, and the tree bark tends to have higher mineral content than other plant materials. Medicinal herbs may actually help prevent lead toxicity. In the Korean Journal of Nutrition (2005; 38 (5) 380-385), a report was published about rats fed high levels of lead (amounts similar to that used in the studies which resulted in lead being controlled by Proposition 65); if they were also fed mulberry leaf powder (mulberry leaf is one of the Chinese herbs), the fecal excretion of lead was significantly increased and the accumulation of lead in the blood and organs of the rats was decreased.

Can the lead level of herb products be lowered?

The lead content of soil—that was affected strongly during the last half of the 20th Century by industrial and automotive use of lead—will decline gradually, and plants will eventually have less content of lead as a result. However, because the levels required by Proposition 65 to avoid warning labels are so low, this change will not alter their regulation in California. Once lead is in the plant materials, it can’t be removed. It is possible to make various extracts of herbs that might leave a larger portion of the lead behind in the portion thrown away, and this can be done with alcohol extraction. However, along with leaving behind the lead, several of the desired active ingredients may also be left behind. Some tinctures are very low in lead, but also provide very little other materials from the herbs, and are labeled with very low dosing, so they may avoid Proposition 65 warning labels (based on total daily lead intake) but they also provide almost no active components.

Is Proposition 65 being challenged?

A. There have been theoretical challenges (that is, questions raised but not brought to legal action) over Proposition 65, mainly on the basis that it sets California standards differently than the rest of the states. However, while it would be of benefit to make changes to Proposition 65, the only practical change that can be made is to repeal it, and there are many supporters of its basic function, which is to improve water quality and food safety by limiting exposure to a long list of chemicals that the EPA has decided might create a risk. Since Proposition 65 has been around for 20 years now, chances are that it will stay as it is. Possibly a better national law will one day come into effect that would permit Proposition 65 to be overturned without substantial loss of its beneficial aspects. Other challenges have been considered, such as exempting specific categories of products, but because of the expense and technical difficulties involved in doing so, this approach has not been pursued. As of 2005, it was reported that there were over 250 substances listed as actionable under Proposition 65, that over 4,000 individual companies were provided notices, and more than 99% of them settled out of court. Proposition 65 was drafted by an attorney with the Environmental Defense Fund; he wanted to shift the burden of safety proof to the producers, and succeeded. Since it is virtually impossible to prove safety, the Proposition forces legal settlements.

Appendix: Sample of Food Analysis

It is difficult to find comprehensive food analytic data that includes the measurement of lead content. Most analysis is conducted by the companies involved with food manufacturing and the results are kept as private, internal documents. Following is data from a published study of a food used in Africa called masa. The typical ingredients are here analyzed (see table below): rice; millet; rice plus cowpea; rice plus cowpea plus groundnut; millet plus cowpea; rice plus millet plus cowpea. The last item in the data table is trona (also called kanwa); it is a natural mineral substance rich in sodium sesquicarbonate, which is used in making the masa food). The rice, millet, cowpea, and groundnut are all common food plants. The calcium and phosphorus figures are given in mg (for a 100 gram portion), so to get ppm (parts per million) it is necessary to multiply those figures by 10. Calcium and phosphorus are nutrients typically present in substantial quantities in foods, as are magnesium and sodium. There are also trace elements, both heavy metals that are of concern, such as lead and cadmium, and those that are considered of nutritional benefit, such as copper, zinc, iron, manganese, and chromium.

Of the trace elements monitored, cadmium is not detected in any of the samples. Cadmium is typically found in plants where the soil is directly contaminated from lead manufacturing, so this suggests that the lead is primarily from natural sources (including airborne contamination from general sources). Chromium content is very low in the plant materials, but is found in the mineral substance trona. Lead is present in all the plant materials in amounts ranging from 0.5 ppm to 1.8 ppm, with an average value of about 1.1 ppm from the six different samples. This level is consistent with what is found in Chinese herb formulas, which (see details given above) have 0.15 to 1.5 ppm, with a typical value of 0.8 ppm. Masa, a major food item, would be normally consumed at 100 grams or more in a day; the lead from 100 grams of masa would range from 50 to 180 ug (micrograms) from the plant materials, depending on the blend. By contrast, 12 grams of Chinese herbs in tablet form (about 18 tablets), would yield about 10 ug of lead (if at 0.8 ppm average), far less than in the masa food. Proposition 65 allows for only 0.5 ug of lead in a daily dose of a product.

Mineral composition of formulated masa blends and trona (kanwa)

Constituent |

Masa ingredients |

||||||

Rice |

Millet |

Rice-cowpea |

Rice-cowpea-groundnut |

Millet-cowpea |

Rice-millet-cowpea |

Trona (kanwa) |

|

Calcium (mg) |

32.0 |

29.0 |

27.4 |

28.9 |

30.4 |

24.3 |

258.5 |

Phosphorus (mg) |

125.0 |

103.0 |

167.6 |

159.1 |

129.1 |

125.6 |

773.3 |

Iron (ppm) |

36.0 |

80.4 |

44.9 |

36.0 |

79.9 |

54.5 |

1,397.6 |

Lead (ppm) |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.5 |

1.0 |

1.5 |

1.8 |

9.8 |

Copper (ppm) |

3.0 |

4.0 |

2.5 |

2.0 |

3.0 |

2.0 |

19.7 |

Zinc (ppm) |

18.0 |

46.9 |

19.5 |

20.0 |

39.4 |

33.5 |

ND |

Cadmium (ppm) |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

Chromium (ppm) |

0.8 |

0.8 |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

39.4 |

Manganese (ppm) |

9.0 |

3.0 |

10.0 |

11.5 |

5.0 |

6.5 |

39.4 |

Magnesium (ppm) |

1,299 |

699 |

1,996 |

2,997 |

898 |

899.5 |

5,905.5 |

Sodium (ppm) |

1,499 |

1,596 |

1,397 |

1,499 |

1,596 |

1,599 |

15,748.0 |

July 2007